In our series on the challenges of family offices choosing to directly invest in companies, we have considered the human capital of a family, the competitive landscape of M&A, and the challenges of deal sourcing. The next logical step would naturally be the process of actually doing a deal and getting to the closing table. This stage is fraught with difficulties. After identifying a target, the would-be buyer must engage in comprehensive due diligence to verify what they are being sold. This should include a variety of deep dives on the books of the company, the potential environment liabilities, etc. For today, we are going to skip the due diligence process and assume that has been well done. Instead we are going to focus entirely on the question what price to pay.

It has been remarked that valuation is both art and science. Certainly, the mathematics involved in discounted cash flow analysis or a dividend discount model feels ‘science-esque.’ But knowing what number to use and how apply the tools is where the art of valuation comes to play. Great books have been written exploring both sides – McKinsey’s Valuation is generally considered to be the best.

Today, we are going to consider what a valuation represents and the implications of valuation to the business owner and the would be acquirer.

At the highest level (disconnected from the day to day operating responsibilities) a business is simply a highly complicated machine that takes key inputs, transforms them into a product or service, and sells them for cash – i.e. a business is a machine that produces cash. The question is how good a job this machine does in converting inputs into cash output.

One way to measure this is calculate 2 common rations – return on invested capital (ROIC) or return on equity (ROE). ROIC is a favorite measure because it looks at the level of investment required for the machine to produce cash – it tells the observer how productive the machine is. ROIC is then adjusted to reflect capital structure to generate a Return on Equity. For the person who started the business and has held it to present day, ROIC/ROE tell the owner the effective rate of return they are generating by continuing to hold their capital in an investment in the company.

When the business goes up for sale, these return measures effectively get brought to the market to see what the market views as the returns a business like this should generate. In that ‘auction-like’ process where multiple buyers compete to buy an asset, a consensus view of value will emerge. And as we looked at in week 2, with the number of market participants out there, even if a formal auction is not being run for a business, there is enough competition to ensure that pricing is fairly efficient. I.e. if you are getting a good deal, it is likely because of some underlying factor, not your luck in finding it.

So, What Would You Pay?

If you were to be offered the chance to buy such a machine, there are a host of questions you would like to understand about it. How well does the machine run? What are the inputs required to produce the cash? Can it be improved to produce more cash? How long will the machine run before it breaks down and how expensive are repairs? Will it be made obsolete at some point and no longer be usable? While valuation is ultimately a price for the machine, it also represents the summation of the answers to all the questions above about the machine.

It also represents a few additional inputs about the buyer itself. Buyers ultimately have many competing places that they can put their capital to work, as such, they expect to be rewarded for taking on commensurately greater and greater levels of risk. Valuation reveals how ‘at-risk’ they believe the investment to be – do they consider the investment to be equity-like or debt-like in its behavior?

Obviously, someone buying a company is making an equity investment, but it is not all together uncommon for someone to view the stability of a company and its cash flows as generating equity returns as almost bond-like in nature. For example, the returns from consumer staples companies for many recent years have been treated in such a way.

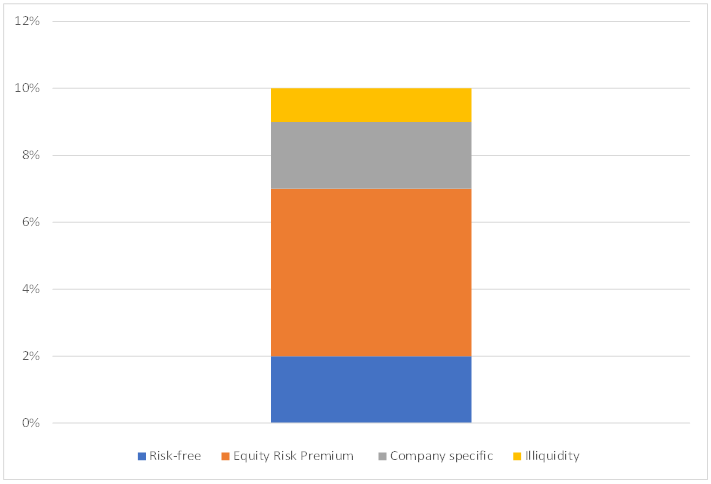

The return required for an investment is ultimately a buildup of varying level of risk. An investor can choose how far up the risk curve to move to put capital to work. Most importantly, it means that acceptable returns have a floor of value – i.e. a minimum required return. For most, this minimum return is the risk-free rate + the market risk premium, i.e. the return offered through a broadly diversified pool of stocks.

More simply, any investor can go buy the S&P 500 for basically free and get access to a diversified source of returns that is highly liquid. A corollary implication of this is that in free market economy, companies that earn rates of return materially higher than this floor rate of return are most likely to see new companies enter the market in order to slowly converge the returns of the company back to this floor return. The genuinely great businesses are ones that continue to earn these returns despite competitive forces.

Figure 1. Example Build-Up of Required Rate of Return Components

Prior to a deal, the business is generating a certain ROIC/ROE which effectively the current owner is receiving. The buyer wants to purchase that return stream, and likely has to offer the current owner some sort of premium for parting with it. Keep in mind what is happening from an accounting perspective when this occurs. In an equity purchase, while net assets are written up to fair value, a sizable portion of the transaction is landing on the asset-side of the balance sheet in the form of goodwill.

The alchemy comes when the buyer is able to offer a price the seller finds acceptable, but still generate a compelling return as an equity holder. In the 1980s, financial buyers discovered that they could offset the drag from investing more capital in a business (i.e. carrying higher goodwill) by adjusting the capital structure of the business. By increasing debt as a % of the overall capital stack, the high ROE of the business could be maintained, even if the higher purchase price saw the overall ROIC get drawn downward.

This juicing of equity returns from higher debt is not without cost. While equity returns can vary, debt holders expect and require consistency of their cash flow. High debt makes corporations more brittle when they approach volatility, which is why so many highly levered businesses have found the current pandemic so challenging to navigate.

So what does this all mean for the family office doing direct deals?

The first implication is that there is an exceptionally high cost to doing mediocre deals. For families who overpay for deals, closing such a transaction require them to either put on too much debt (and risk a more catastrophic loss) or commit too much equity. It is in fact the latter that represents the signficant drag that comes from mediocrity. Too much equity drags down the ROE of the business towards an equivalent rate of return the family could access in the public markets. With public market returns being low cost to access, exceptionally diversified, and highly liquid, receiving the same returns but in a direct deal is the height of foolishness. Not only are those returns demonstrably more risky than owning the S&P 500, they represent the forfeiture of the ability of the family to be opportunistic to access better returns when market conditions drive forced sellers to market and bargains abound.

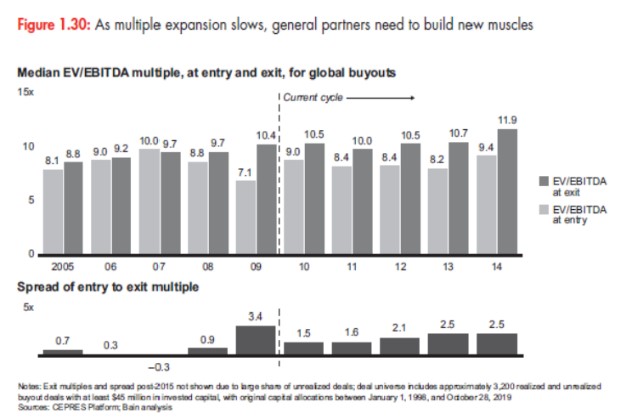

Second, the multiple expansion bail-out is past – lower returns likely ahead. One of the great boons to returns in recent years has been the ability to acquire at one multiple and sell at a significantly higher one. This additional value can take a mediocre deal and make it satisfactory, and take a satisfactory deal and make it extra-ordinary. The Figure below outlines just how sizable this benefit can be.

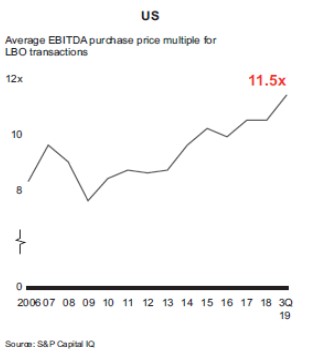

But the ability to sell at a higher multiple is contingent on the entry price paid. And as can seen from below, pricing for businesses has been on quite a run since the Global Financial Crisis. As such, for business buyers that were baking in multiple expansion to hit their return targets, they will now be faced with finding other ways to reach returns.

Third – if multiples retreat – families will have to push hard for growth. Consider then a hypothetical example of a $100MM revenue business with 20% EBITDA margins that is acquired for 11x times. Assume that on exit, the investor is not able to sell the business for 11x and that exit multiples have mean reverted back to 8.5x. How fast must the company’s top-line have grown for an investor in a private equity fund (and paying full fees) to generate a 15% return net after taxes? The answer is nearly 18% a year over an assumed 7-year hold.

The question then is – how many $100MM revenue companies have close to 20% top-line growth opportunities available to them? Intellectually honesty, would dictate that the appropriate answer to that question is that it depends. No doubt there are many rapidly growing industries with significant amounts of organic growth available. However, for many mature industries this late in a market cycle, growth will be hard to find. The bottom-line implication is that in such a rich multiple environment, return expectations will have to come down – further raising the bar for anyone choosing to do a direct deal.

Conclusion

The resounding theme of the four parts of this series thus far is that families who choose to do direct deals are choosing to trod difficult ground. This week we have considered how the price paid for a deal ultimately affects the return realized. We recognized that when a transaction occurs, the ‘cash-machine’ of a business gets priced at a market rate of return. For families to earn high rates of return after the deal, there are only a few opportunities available – capital structure, multiple expansion, and growth. At this portion of a market cycle, none of these are easy. Most importantly, we highlighted the high cost of mediocrity. Giving up liquidity and diversification is not something that should be contemplated lightly, especially considering the opportunity costs of not having access to capital in turbulent times.

Disclaimer: This does not constitute investment advice or an offer to buy or sell any securities. It is provided for informational purposes only and represents the author’s own opinions